By Edward Klorman (McGill University)

Author’s note: This blog post is adapted from Chapter 6 of my book Mozart’s Music of Friends: Social Interplay in the Chamber Works (Cambridge University Press, 2016).

When examining a metrically ambiguous passage, many musical analysts will seek to untangle problems by explaining which among multiple metrical interpretations is “the correct one.” In this blog post, I explore metrical conflicts from a different point of view—namely, that of the performers.

Musicians often strive to find ways to play better together, to match their phrasing and shaping in order to “feel” the music in a unified way. But what happens when they encounter a passage in which their parts don’t match, but are in conflict? The subordinate theme from Brahms’s Sonata in E♭ Major for Piano and Clarinet, op. 120, no. 2 is a case in point.

You can get a sense of the issue—and imagine how you might approach it in performance—from this video. (Since my clarinet skills are a little rusty, I perform on viola instead!)

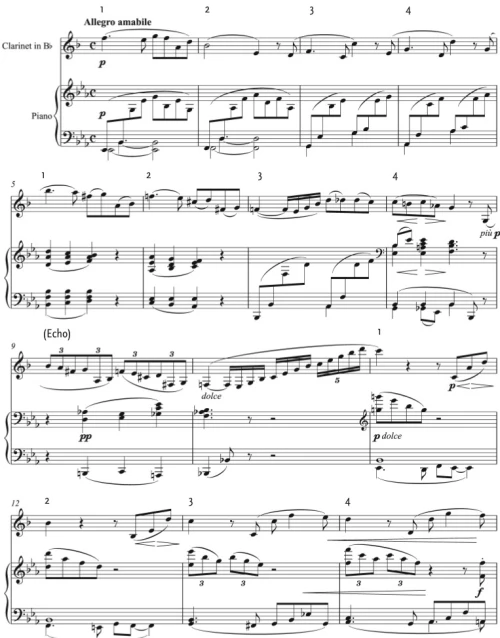

To provide some context for the subordinate theme, let’s first look briefly at the main theme and transition. The sonata opens with fairly regular four-bar hypermeter, as I’ve shown in my markings above the staves.

Some metrical dissonance arises in mm. 15–17, which tend to sound more like 3/2 meter than the notated 4/4. Within these four bars, the piano’s left hand emphasizes the off beats, playing on the weak quarters of each half-note pulse. The four-bar hypermeter is restored in mm. 18–21, but the piano’s syncopations continue to emphasize weak quarter notes. (These syncopations foreshadow an ambiguity I will discuss in the subordinate theme.)

In m. 21, the final bar of the transition, the diminuendo hairpin and the rest on beat 4 encourage the players to use some rubato, allowing the sound and momentum to dissipate as the passage comes to rest on a tentative German augmented-sixth chord in B♭ major (a harmony that yearns to resolve to V in the new key, the traditional cadential goal of an expositional transition).

And then what? After the general pause, the clarinet begins the subordinate theme on the notated downbeat, with the piano imitating one beat later.

The Subordinate Theme in Brahms’s Notation

This imitation constitutes a canon per arsin et thesin, whereby strong beats in one part coincide with weak beats in the other. Coming right after a general pause, this passage would challenge many listeners to determine whether it is the clarinet’s entrance or the piano’s that falls on the “true” downbeat (if the listener is not following the score).

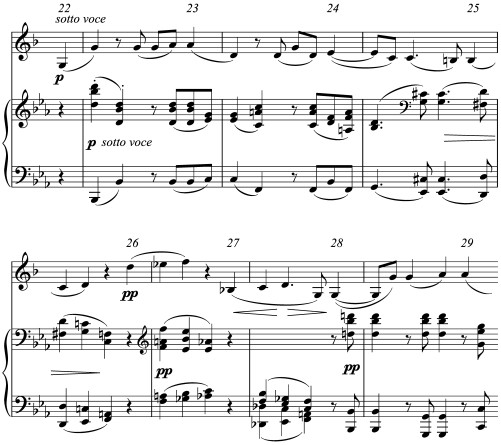

Indeed, for the first several bars of the theme, it seems plausible that the bar lines might be located one quarter note later than how Brahms notated them, as shown below. Only by m. 28 (best seen above, in the print of Brahms’s score) is the notated bar line unequivocally confirmed: the clarinet’s eighth-note upbeat clearly establishes the downbeat of m. 28, and moreover it is at this juncture that the piano gives up the metrically ambiguating canon. Simply put, my alternative notation below seems plausible initially at m. 22 (making the placement of bar lines difficult to discern for several measures), but by m. 28 it is absurd.

Subordinate Theme in a Plausible Alternative Notation

Why do I hear this passage as so metrically ambiguous? And how should musicians approach their performance of such a metrical conflict? I will explain my own understanding and performance approach:

After the German augmented-sixth chord and general pause in m. 21, the clarinet’s entrance on concert F may initially seem to represent dominant harmony, bolstering the sense that it is an upbeat to the piano’s tonic entrance. But when I play the passage (on viola), I try to make the entrance in a metrically neutral way, stressing neither note of the (concert) F–F gesture. Observing Brahms’s sotto voce marking and emulating a clarinet’s capacity for niente entrances helps to achieve this. Once the piano enters in canon, the two players might emphasize their conflicting meters with a gentle persistence—that is, with the piano emphasizing the long slurs beginning on beat 2 (and thus suggesting my alternate notation). Brahms’s beams across bar lines encourage the pianist to count in terms of my alternate notation. This performance approach heightens the conflict and suspends the sense of metrical ambiguity as long as possible (ideally until around m. 28), thus taking advantage of a special opportunity afforded by Brahms’s passage.

* * *

The approach I’ve suggested here is consistent with performance advice proffered in eighteenth-century performance manuals, such as those by Leopold Mozart, Johann Joachim Quantz, and Daniel Gottlob Türk. These authors encourage performers to emphasize beginnings of slurs, especially those that are syncopated against the meter (as in the piano part here). Brahms was certainly familiar with these ideas and harbored a highly traditional understanding of the meanings of slurs, one that is particularly relevant in a passage such as this. (On these eighteenth-century writers’ understanding of slurs and their execution, see my discussion in Mozart’s Music of Friends. On Brahms’s affiliation with older understandings about slurs, see Heinrich Schenker’s essay “Abolish the phrasing slur” in The Masterwork in Music, I [1925]).

I’ll close with a perspective on performing metrical conflicts from an author more nearly contemporary to Brahms (and certainly one who felt a strong affinity to him), Heinrich Schenker:

It is the responsibility of the performer primarily to express the special characteristics of a composition, as they sometimes coincide with the meter, sometimes oppose it. Today, not only the failure to recognize rhythmic relationships but also sheer indolence creates a performance for the metric scheme alone—a dismaying evidence of decline (Free Composition, translated by Ernst Oster, emphasis added).

Leaving Schenker’s hortatory tone aside, he offers an idea well worth pondering. In everyday life, we strive to avoid conflicts or else to resolve them. But in playing music, our impulse to resolve conflicts should be questioned. A conflict-resolving performance strategy might conclude: “Brahms clearly intended the meter as he notated it, and this is confirmed by m. 28. Therefore, we should perform in accordance with the notated meter, minimizing signals that rub against it.” But a more satisfying approach, at least to me, is to allow the conflict to flourish and for the two musicians to each make an earnest bid for the meter as suggested by their own parts. The clarinetist’s bid for the notated meter ultimately prevails, of course. But our final-state understanding of the metrical structure is, like history, determined by the victor, and only after the conflict has ended.

Dear Edward,

Your analysis (and wonderfully sensitive performance) resonate with my experiences as a young clarinetist (rather a while ago). When I first played this, I recall the necessity of a “gentle persistence” simply to remain afloat, let alone to promote the delightful metric interplay you elucidate here. Coming back to this piece years later, I find myself able to relax into this metric conflict and find a kind of comfortable discomfort that I’ve learned to love in Brahms.

I’ve felt this conflict viscerally in several of Brahms’ late solo piano works–especially Op. 116 No. 1 and Op. 118 No. 5–where sometimes both hands appear united against the notated meter and other times the left and right hands are at odds. A wonderful earlier example with a similarly spirited play occurs in Beethoven’s Bagatelle Op. 33 No. 2, about which Janet Levy (1992) and I (2015) have written. While Beethoven’s lends an impression of an almost mechanistic glitch, Brahms seems to weave his metric play more intricately into the fabric of his works. At risk of an over-generalization, it seems to me that the attributes we often accord the two composers’ individual personalities are particularly evident in their metric play in these works: Beethoven, with a mechanical, stubborn force; Brahms with a somewhat restrained, yet rhapsodic insistence.

Thank you for posting your analysis here!

Sincerely,

James Palmer (University of British Columbia/Douglas College)

LikeLike

Jim, really interesting to hear about your experiences playing this piece! “Comfortable discomfort” is a nice way to put it (comfortable or gentle because of the sotto voce, but uncomfortable because of the metrical conflict and ambiguity). I know what you mean about the relation between these pieces and late Brahms piano pieces. I’d love to read what you’ve written about the Beethoven bagatelle.

LikeLike

Thank you for your great analysis! One detail: While I can see that, in a general way, it is a canon per arsin et thesin (that is to say, the time interval of imitation is half as long as the metrical unit—the half note), I hear it rather as a four-beat unit (a measure unit) displaced by a quarter note. In Krebs’s terms, it’s a D 4+1 dissonance (1=quarter). If you hear it that way, the displacement dissonance produces a greater degree of conflict, since, the shorter the time intervals, the more intense the dissonance. I think that, in this performance, you both do that—you emphasize each downbeat, in your respective four-beat “measures,” rather than every second quarter note beat. This may be a reason why the opposite metrical pattern—the one where the strong beat occurs right before the rest—sounds so “wrong” for each individual instrument (that’s how it sounds to me, anyway): a true “per arsin et thesin” canon, with an equal division of the metrical unit, and usually of the imitated motive too, rarely sounds so “off”—that is, so conflicted with the other part.

LikeLike

Ellen, really interesting point! I hadn’t considered the distinction between a true canon per arsin et thesin vs. a D 4+1 dissonance, and I take your point that it’s an important one.

LikeLike

Funny coincidence, my forthcoming book Focal Impulse Theory (IU Press), which deals with the role of meter in performance, will also talk about this passage, and it will also feature a performance by the author on viola, unless I decide that the performance isn’t good enough, a very real possibility especially after hearing Ed’s!

My way of dealing with the conflict is quite different. I like Ed a lot and have great respect and enthusiasm for his work, but at the end of the day there aren’t very many passages of common-practice music in which having performers tugging toward different metrical interpretations appeals to my personal taste. (As it happens, those I can think of are also by Brahms…)

Instead, in my interpretation the piano part is performed using a motion that’s based on anticipations – putting the kind of weight behind the weak beat that’s usually given to the strong beat, but then instead of releasing the weight right away, sustaining the moment of impact until the strong beat and then releasing. (Sorry for the mixed metaphor, but I hope some hint of the concept comes through.) It’s easier to do when the note is actually sustained, harder in cases like this where the note changes on the downbeat. But it can be done, and it gives the weak beats a special kind of weight and accentuation which sounds quite different from a rebarred performance.

I also agree with Ellen that it’s important to observe the difference here between a 50% and a 25% phase shift. Related to their relative salience, the 50% shift has a long history (great intro for those not familiar in a Floyd Grave article in Theoria from ’85) that the 25% shift lacks. Originally part of the book on meter in performance, now a second projected book (on Brahms), I’ve looked at metrical dissonance in every work of Brahms with an opus number, and based on my hearing (or my guesses about likely hearings) the 50% shift is far more prevalent than the others – though many others are used as well. (I should specify that I’m talking only about shifts of heard meter, if I tracked every canonic imitation I’d never have finished the survey.)

And this brings me to a question for Ed (perhaps answered in the book) of what kind of parameters there are around the appropriateness of this kind of metrical rivalry among parts? I think my favorite canon in Brahms is a simple 50% phase shift relative to the measure – but in 3/4! It’s the canon between clarinet and violin 1 in the slow movement of the clarinet quintet, a canon at the seventh to boot. On the face of it, it should never work in a million years, and in actuality how it works is comparatively simple as Brahms’s canons go. But – would you want the first violinist to try and hear as if starting on a downbeat in 3/4, and to play accordingly? For me, this is a great example of one facet of Brahms’s love of ambiguity, allowing something to retain its identity at a basic level, while on another level turning it into something utterly different – here, melodically, harmonically, metrically, and expressively.

LikeLike

John, thanks for this interesting comment, and I can’t wait to read your discussion in your book. (I hope you will indeed include your performance!) That’s interesting to read about your corpus study of displacement in Brahms and about the rarity of a 25% shift, as in this example. That canon in the slow movement of the clarinet quintet is pretty remarkable. Another favorite of mine (and one that every violist knows) is in the first movement of the Piano Quartet in C Minor, in the retransition: the viola starts a tune in m. 177, imitated by the violin one 3/4 bar later; then in m. 185, the viola restarts the tune, and the violin imitates just two beats later; and finally, in m. 191, the viola tries a third time, with the violin now imitating just one beat later, and the piano entering one beat after that (with the chordal ninth!). I’m struck in this passage that the violin seems to “choose” to imitate at closer and closer time intervals, causing more tension against the 3/4 meter and contributing to the sense of rising tension.

In my book, I cite some passages from eighteenth-century performance treatises that encourage musicians to emphasize these sorts of syncopated entrances. The examples I cite are typically involve syncopation against the meter (not syncopation against other instruments). I do give a number of examples in my chapter of instruments syncopating against one another, some of which seem to imitate the sound of choral sections imitating each other antiphonally (as in the overlapping entries of “Hallelujah!” in Handel’s Messiah). See my discussion of the end of Mozart’s K. 387 finale, which I describe as an example of the same sort of thing, imitated by a string quartet. Another example is in the Minuet movement from Mozart’s Clarinet Quintet, in the first trio (in A minor): I note that all instruments have two-beat slurs, some from beat 1 to 2, other from 2 to 3, and still others from 3 to 1. I enjoy the kaleidoscopic effect if each instrument gently pulses its individual slur (and miss the effect if everyone plays totally seamlessly). If you have a chance to look at that chapter, I’d be eager to hear your take on it!

LikeLike