By Nancy Murphy (University of Houston)

This post serves as a preview of a lightning talk that will take place at PAIG’s 2019 SMT meeting in Columbus (Saturday, November 9 from 12:30 to 2:00 pm).

The study of expressive timing typically observes how notated metric structures are varied in performance. Expressive asynchrony is one such method of variation in which performers desynchronize notationally aligned events. Previous studies—like Yorgason (2009) and Dodson (2011)—have observed this technique in performances of nineteenth-century piano music. In the paper I will present during the Performance Analysis Interest Group meeting at SMT this weekend, I examine asynchrony as a technique of lyrical expression in two performances by Canadian singer-songwriter Buffy Sainte Marie: “Winter Boy” from Little Wheel Spin and Spin (1966) and “Ananias” from It’s My Way! (1964).

Sainte-Marie, a contemporary of Bob Dylan and Joni Mitchell, emerged as a self-accompanied singer-songwriter in the 1960s Greenwich Village folk scene. Her songs explore topics of personal significance alongside politically charged narratives that engage her original perspective as a Native American; Sainte-Marie is a longtime activist, and her music is well regarded for the social impact of its lyrics. Her song “Universal Soldier,” a powerful anti-war anthem written as the Vietnam war was escalating, allowed her to speak about individual responsibility for war. Sainte-Marie’s songs also address the mistreatment and inaccurate historical representation of Native Americans. Her first widely popular Native American protest song was “Now That the Buffalo’s Gone”; here she decries the 1960s hypocrisy of Americans condemning past treatment of Native Americans while simultaneously displacing them (for example, by building the Kinzua Dam in New York). Sainte-Marie’s critiques also extended to educational issues; “My Country ‘Tis of Thy People You’re Dying” borrows text and melody from “My Country ‘Tis of Thee,” specifically targeting U.S.-history curricula that begin with the arrival of European colonists.

While singing passionately about her subject matter, Sainte-Marie often uses expressive timing to highlight the meaning of her lyrics. Her song “Suffer the Little Children,” from Illuminations (1969), addresses the impact of residential schools that pushed children and their parents to abandon their culture and language to succeed in colonized society. Sainte-Marie’s performance on the studio recording features ritardandos at significant moments in her lyrics, particularly when she sings about mothers of children in residential schools. She repeats different words of the line “Mama don’t really care” with a slower tempo, as if to scold mothers, but later empathizes with their situation (“Poor Mama needs a source of pride”). These timing fluctuations serve to express Sainte-Marie’s perspective on the subject matter.

My talk explores two of Sainte-Marie’s more personal songs, in which her use of expressive asynchrony highlights the lyrical meaning. This technique of expressive timing is usually heard between the two hands of the piano: for instance, when notationally aligned chords are desynchronized between the hands, or when composed-in events like rolled chords and grace notes elongate beats. When the downbeat of a measure features such an expansion, Brent Yorgason describes this as an elongation of downbeat space: a type of asynchrony that occurs in combination with the sense of arrival associated with downbeats.

Sainte-Marie’s performance of “Winter Boy” establishes a regular meter and then emphasizes specific phrase-unit beginnings by slowing the tempo and elongating downbeat space through asynchrony. At the first mention of the titular “Boy,” (transcribed below) the voice’s syncopated arrival leaves the downbeat unarticulated, and the sense of anticipation increases until the eventual entry of the guitar.

This reading highlights sensations of expectation as Sainte-Marie lingers on and anticipates the arrival of “Winter boy”—after which the meter resumes. She employs similar techniques at several other moments in the song, highlighted below, each serving to express the lyrical narrative.

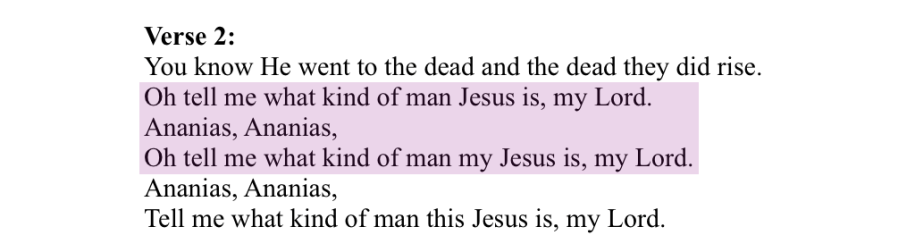

Yorgason’s study also explores large-scale patterns of timing variation: what he calls processes of gradual or diminishing dispersal. In progressive dispersal, events like rolled chords and the increased lengths of notated durations expand beat space. The opposite—what Yorgason terms diminishing dispersal—can be found in Sainte-Marie’s song “Ananias.” Here the song’s goal-oriented narrative of achieving faith is mirrored in its achievement of synchrony, a process I call progressive synchrony. In “Ananias,” asynchrony is part of an expressively timed opening (the opening fragments of which I’ve transcribed below).

Eventually this yields to a coordination between the voice and guitar. As the text affirms belief, the process of progressive synchrony aligns with the shift in lyrical narrative, which can be heard by listening to the refrains highlighted below (click to listen: Verse 1 Refrain, Verse 2 Refrain, Verse 3 Refrain).

These two techniques of expressive asynchrony are not limited to performance of notated piano music. Indeed Sainte-Marie uses them to convey the narratives of her songs. Studying asynchrony in Saint-Marie’s music brings us in closer contact with her broader contributions to techniques of lyrical expression in the singer-songwriter style of the 1960s and 1970s.

These two techniques of expressive asynchrony are not limited to performance of notated piano music. Indeed Sainte-Marie uses them to convey the narratives of her songs. Studying asynchrony in Saint-Marie’s music brings us in closer contact with her broader contributions to techniques of lyrical expression in the singer-songwriter style of the 1960s and 1970s.

As always, comments are welcome. Share your thoughts below!

I’m trying to understand the lyrics of Ananias and it baffles me. The first character, named Ananias, was a man in Jerusalem, who with his wife Sapphira, tried to deceive the disciples of God, by stating that the portion that they had offered to the disciples was all that they had received from the sale of their property. They were both struck dead that very day. The disciples tell Ananias, that he had not only tried to deceive them, but in fact, he and his wife were deceiving God by lying to the Holy Spirit of God. This is Ananias, the liar. (Acts 5:1-5). So why Ananias?

LikeLike